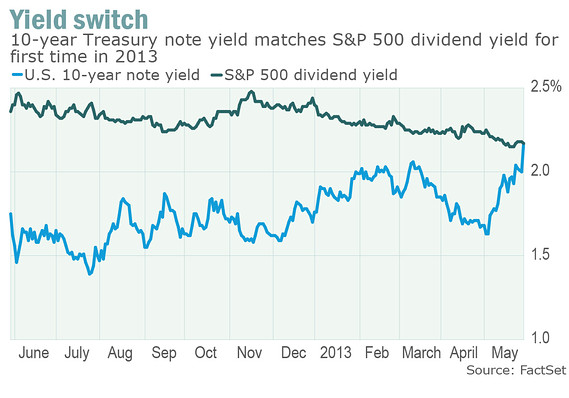

For the first time since 2011 the yield on the 10-year Treasury note now exceeds the dividend yield on the S&P 500. You can see how for the past twelve months, until now, stocks have yielded more than Treasuries. This relative yield argument has been used by many to get investors to jump back into stocks.

Source: Marketwatch

That situation has now reversed. Just how big a deal is this? William Watts at The Tell writes:

After all, dividend yields have historically trailed Treasury yields by a fair amount. The game changed when the Fed moved to lower yields through quantitative easing. Howard Silverblatt, senior index analyst at at S&P Dow Jones Indices, notes that historically the S&P 500 dividend yield has averaged just 42% of the 10-year Treasury yield. That would put the 10-year Treasury note yield at around 4.3% today.

Towards the end of 2011 when I was finishing up writing my book I noted in the conclusion the rarity of having dividend yields exceed the yield on Treasuries. I was nervous putting it in because I feared the situation could quickly reverse. However the markets kept in place this inversion until this week. Back then I wrote:

The war on savers is still ongoing. The yield on short-term Treasury bills is essentially 0%. The yield on a 10-year Treasury note hovers just below 2%. After inflation (and taxes), this yield is almost guaranteed to lose purchasing power over time. The upside of the lost decade for stocks is that it leaves stocks, as measured by the S&P 500, in the enviable position of having a higher yield than the 10-year Treasury note for an extended period not seen since the 1950s! It remains to be seen whether this unique situation represents a return to post–Depression era thinking when equities were viewed to be so risky as to require a dividend yield in excess of Treasuries. In contrast, it might represent a time when equities will once again generate a return over and above risk-free assets.

Maybe that is all that long-term investors can really hope for at this point: a return to some measure of normality. Poor financial and economic performance of late makes it easy for us to extrapolate the poor recent past into the distant future. Historically, poor decades for stocks in general have been followed by better times. For some that may not be enough to go on, but in a certain sense that is all we have. Carl Richards writes: “In some regard, investing based on the weighty evidence of history is the most prudent thing we can do. So far it has always proven to be correct. Every time someone has predicted the death of the stock market, they have been wrong. Given this record, isn’t it reasonable to assume that stocks will continue to be better than bonds, and that bonds will continue to be better than cash?”

That does not mean we should have some naïve faith that the future will hold nothing but good times. A prudent approach to investing always recognizes that risk is inherent in the process. There always is a wall of worry that can prevent us from investing. Then again, what is the alternative? As Jack Bogle said in response to a question about the tough times facing investors: “But the problem is that we must invest. We can’t stand back. If you don’t save anything, I guarantee you will end up with absolutely nothing.”

The past year and half has seen equities outperform Treasuries. The question as always is what comes next? The withdrawal of extraordinary Fed actions will likely have market unforeseen impacts. We have been living in “interesting times” for the financial markets for going on a decade now. So a return to some level of capital markets normalcy would be a welcome change.

Thanks also to @mattphillips, @paulrubio and @lesser_mistakes.