If you have been reading Abnormal Returns the past few days you are well aware of the debate going on between upstart robo-advisor Wealthfront and behemoth Charles Schwab ($SCHW) about the cash position in their new Schwab Intelligent Portfolios. Victor Reklaitis at Marketwatch and Ryan W. Neal at Wealth Management both have good coverage.

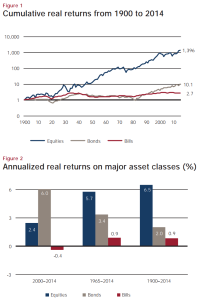

This isn’t about the debate, which per Leigh Drogen, works in favor of the upstart not the incumbent. This post is a broader exploration of the idea of cash and its proper role in a portfolio. First off let’s look at some numbers. The graph below, from the Credit Suisse Global Investment Returns Yearbook 2015, which we note on an annual basis, show the real returns to stocks, bonds and cash in the US since 1900.

Source: Credit Suisse Global Investment Returns Yearbook 2015

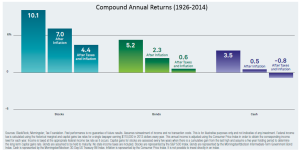

What you see is that over the longest time period cash, as proxied by T-bills, returns 0.9% real annually. However since the year 2000 you can see these returns have been negative (-0.4% annually). Broadly speaking cash hasn’t generated cumulative real returns since 1930 or so. In fact in the chart below from Blackrock you can see that net-net, after inflation and taxes, cash has generated negative returns since 1926.

Source: Blackrock

Russ Koesterich at Blackrock correctly points out the generally poor returns cash provides but notes certain cases when it makes sense to hold including for those with very short time and horizons and in the case of market timers. He writes:

(A) large temporary cash position makes sense for market timers, who believe they have the skills to move in and out of asset classes and profit from such actions. But as the State Street numbers suggest, for many investors it is easier to get out of the market than to get back in.

Josh Brown at The Reformed Broker weighs in on the value of cash in a portfolio and comes down on the side against big slugs of cash as well. He writes:

Cash should be used as either an emergency fund outside of a portfolio (in a bank) or as a tactical position for those who choose to be tactical. But as a permanent sleeve of an asset allocation portfolio, we do not believe that cash makes sense. We tell clients to keep three to six months living expenses in cash on hand, but that anything beyond that is purely emotional or closet market-timing.

However clients with big slugs of cash in their portfolio, whether it be by design or simply luck, are not all that uncommon. David Fabian at FMD Capital Management notes that investors in this situation need to have a plan on how they will eventually deploy that cash and recognize that they will not do so perfectly. He writes that few investors fit this bill:

If you are an active and disciplined trader that has been lightening up on positions into this strength, then you likely have a plan to re-deploy capital at lower prices. In my experience, those types’ of investors are rare to find.

Mebane Faber writing at this eponymous blog weighs in on robo-advisor debate somewhere in the middle with a sensible solution for how to deploy money into a cash-like asset.

I don’t mind cash as a strategic allocation, but I do agree with Wealthfront that Schwab earning revenues from the money market sweep accounts could bias their decision to include cash. There is just no need to do this – they could have used an ultra short term gov bond ETF and still made some money off it. However, the moral outrage from Wealthfront comparing Schwab to Merrill is a little ridiculous considering Wealthfront used to charge 1.25% for access to “geniuses”.

The funny thing about this cash debate is that is occurring at a time when the Federal Reserve seems to be getting ever closer to raising short-term interest rates and by extension breathing some much needed life into the moribund asset class that is cash. Cash shines in a time of rising short-term interest rates.

That should not give investors comfort with big strategic allocations to cash. As we have seen earlier there is little historical basis for cash providing investors with much more than steady purchasing power. When it comes to the temporary, tactical use of cash it again is problematic. Few investors have the wherewithal to both get into and out of cash on a disciplined basis. As I wrote in this post:

Market timing is a gateway to cash addiction. One need only look at fund return statistics to see that individual investors have a horrible tendency to buy high and sell low. Have a strategic (or even tactical) asset allocation and stick to it. Let the “professionals” wield cash in an option-like fashion. You have better things to do with your time.

This behavioral argument in fact underlies the attraction of robo-advisors for the vast majority of investors. Robo-advisors take the cash vs. no-cash decision, and many others, off the table. A disciplined portfolio strategy, even if sub-optimal, is better than an ad hoc portfolio strategy. For DIY investors cash represents a bad habit they need to kick. For investors shopping among the many robo-advisor solutions it simply represents a feature they need to better understand.