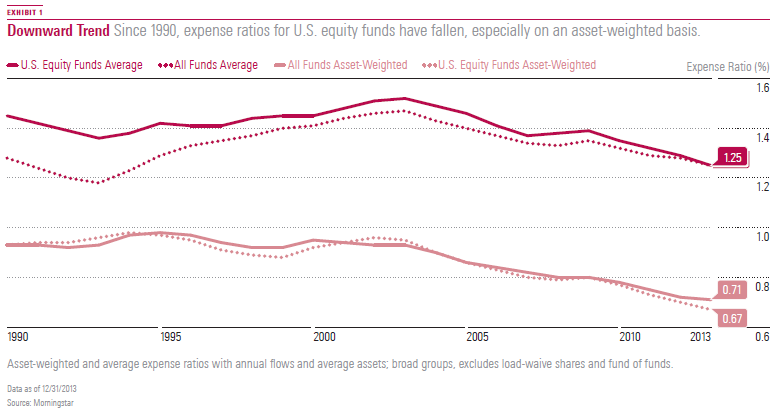

Depending how you look at it the expense ratio for US equity funds have been dropping for either one decade (or two) depending on how you measure fees. The question is why? In part this is due to investors increasing preference for index funds, which on average have lower expense ratios. Also one could argue that this is an example of competition working, albeit slowly.

Source: Morningstar

A recent paper, Indexing and Active Management: International Evidence by Cremers, Ferreira, Matos and Starks, shows that in countries where index funds are more prevalent, the fees on actively managed funds are lower and the results on those funds are better. The argument being that in countries where closet indexing is commonplace there is little incentive to try to generate better performance either through lower fees and/or better management.

Another example of competition working is through the rise of so-called ‘smart beta.’ This FT article talks about how managers are seeing fee pressure due to the increased use and acceptance of smart beta funds. In short, if managers are unable to demonstrate alpha over and above funds with similar factor loadings they are increasingly out of luck.

By all accounts 2014 was a horrible year for active managers with only 13% of all domestic equity funds outperforming the broad market. The question is whether it is going to get any easier for managers going forward. While there were many cyclical factors working against active managers in 2014 including poor relative small cap performance and little utility to cash. Unfortunately the secular trends all seem to be working against them as well.

Josh Brown at the Reformed Broker has a longish piece looking at this phenomenon. One argument against things getting better for active managers is that there is simply not as much “dumb money” out there. Josh writes:

I’ve just finished reading the excellent new book by Larry Swedroe, The Incredible Shrinking Alpha

, in which he lays out the evidence for why active management isn’t working for investors and some reasons for why it will only get harder, not easier, going forward. One of the more interesting ideas he has is that the exodus into passive strategies – which is usually cited as a reason for active outperformance going forward – is actually a major negative. This is because, with all the unskilled investors departing, pros will be left to square off against only other pros. The lack of retail punters and their harvestable mistakes cuts off one of the most reliable historical sources of alpha for sharp-eyed managers.

If you buy this argument not only are passive index funds putting pressure on fees, they are also leaving fewer opportunities for active managers to outperform. Those that do remain are going to have to be able to show some differentiation between themselves and the indices. One common measure of this is active share. Expect to see more and more emphasis on this from managers in the future.

Between index funds and the rise of ETFs we have seen a sea change in the world of investment management. Investors can now, with not a whole lot of work, assemble a diversified portfolio of ETFs with a blended expense ratio of less than 0.10% a year. That is essentially having your money managed for free.

It took a long time but the introduction of the SPDR S&P 500 ETF ($SPY) back in 1993 and the relentless rise of Vanguard Investments has ushered in a very different era for investors. By all accounts it has become a more difficult time for undifferentiated active managers burdened with high expense ratios. But for the rest of us, there has never been a better time to be an investor.