Abnormal Returns readers are by now already familiar with Wes Gray (@alphaarchitect) of Alpha Architect. We have published Q&As with him on the publication of his co-authored books Quantitative Value and Quantitative Momentum. Wes is becoming quite the media star of late with a profile in the WSJ and a recent WSJ post highlighting some research blogs you should be reading.

We were lucky enough to catch up with Wes and his colleague Jack Vogel (@jvogs02) to discuss their new ETF* and some lessons they have learned about the ETF business along the way. Our discussion of the Value Momentum Trend Index process is timely because it covers the most interesting and well researched “anomalies” out there: value, momentum, and trend. Of course, the Index itself is fairly complex so I wanted to get the sources to help me better understand what was going on.

As we went through the interview we engaged in a lot of non-product related questions that are on the minds of almost every investor these days. Can investors time factors? Have factors been arbitraged away? How are ETFs affecting the market? And what it is like to run an ETF operation. Our discussion is fairly detailed, worth the effort. Enjoy.

AR: Gentlemen, walk me through the mechanics of your Value Momentum Trend Index methodology.

JV: As the name implies, we are trying to combine three factors we consider to be the most robust:

- Value

- Momentum

- Trend

We use Value and Momentum for the security selection portion of the portfolio—the idea here to capture focused global value and momentum equity premiums. In this process we want to avoid closet-indexing; put simply, our Value and Momentum Index methodologies are unique and definitely not for everyone. When it is all said and done, the underlying equity portfolio in the Value Momentum Trend Index is around 180-200 stocks. We access these exposures in a real-world context by holding our four underlying ETFs (QVAL, IVAL, QMOM, and IMOM).

Source: Alpha Architect

AR: Okay, I get the Value and Momentum pieces. How about the trend component?

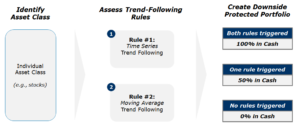

JV: Sure. As you mentioned, the final ingredient for our Index is the trend-following component. We use long-term trend-rules to determine the level at which we need to hedge the portfolio’s beta. The two rules we use are a 12-month moving average rule and a 12-month time-series momentum rule (the two are related but not the same). The rules are assessed separately to the US and International portions of the portfolio. (Here are some details on our trend-following system).

If the trends are positive, we are long-only. When the trends turn negative, we start to layer in hedges on the portfolio. And if trends are all around negative, the portfolio can become essentially market-neutral (i.e., fully hedged). This dynamic beta exposure of the portfolio is somewhat unique in the liquid alternatives space. A few other firms run trend-following systems in their funds (e.g., Cambria, Pacer, and AlphaClone).

Hopefully we conveyed a high level overview of the Index methodology. If someone wants to learn more, we just finished an exhaustive discussion on the Index process via a detailed post. We try to be as transparent as possible and encourage folks to let us know if something is confusing about our process.

AR: The VMOT Index has a lot of moving parts. Who is the ideal investor for the strategy?

JV: We agree there are a lot of moving parts, and this program took us over 5-years to fully develop. We’ve made it as simple as possible, but no simpler. In the end, the Index’s intuition is fairly simple: capture concentrated global value and momentum premiums, while simultaneously attempting to minimize the risk of massive drawdowns.

All that said, we recommend that anyone interested in the strategy fully understand all the moving parts, as the strategy has 3 aspects that will cause it to deviate from a standard benchmark and there is potential for massive tracking error. The appropriate benchmark for something like this is arguably a global long/short hedge fund index or a portfolio that is around 50% cash and 50% in a passive global equity portfolio (the beta on the Index is around .5). Of course, many will actually benchmark the Index to the S&P 500. Investors might be surprised if they go down that path, so having appropriate expectations is important, which is why we are as transparent as possible about the Index methodology.

The tracking error of the Index relative to the S&P 500 will come from 3 parts of the portfolio:

- The portfolio is roughly 50% US and 50% developed stocks.

- The portfolio invests heavily in relatively concentrated portfolios of value and momentum stocks.

- The portfolio uses trend rules, which cause the portfolio to have a dynamic beta over time.

In other words, this Index might be all over the place will not directly follow the S&P 500. From a diversification standpoint, this is a good thing, but from a short-run relative performance standpoint, this could cause a lot of angst. In short, this is a complex strategy that is most appropriate for sophisticated buyers with a solid grasp of portfolio theory and factor investing.

AR: What are the competing concepts out there?

WG: As we mentioned above, there are a few other publicly available strategies that follow a similar methodology. For example, Cambria applies Value, Momentum, and Trend in one of their ETFs, VAMO – but this ETF focuses only on US stocks. Another Philly firm, Pacer Financial, also offers ETFs that follow trend rules to time broad diversified market exposures. Aptus Capital Advisors runs a concentrated large cap strategy that runs from 100% to 100% bonds (when needed). A fourth option for investors is AlphaClone, who run a product that owns a fairly concentrated portfolio of activist plays and stocks owned by “smart money” investors. They manage the beta on their portfolio via trend following rules. There may be some more options out there — and there are plenty of them in the hedge fund space and liquid alternative mutual fund space — but there aren’t many that are embedded in the tax-efficient and fully-transparent ETF wrapper.

In addition to the publicly available options, we have come across numerous financial advisors who tend to apply some sort of trend-following overlay on long-only equity exposures. The strategies listed above essentially free up advisors using trend rules so they can focus on higher value-add activities with their clients.

AR: There has been a huge debate of late about whether factors, like value and momentum, can be timed. That debate largely centers on valuation. Can factors be timed and is it worth it?

JV: Many have argued for and against factor timing – in general, the context is whether or not one can time long-only factors such as Value, Momentum, Quality or Low Volatility.[1] This has received a lot of press recently as Low Volatility has been a factor that has outperformed, while Value has lagged the market.[2]

WG: Listen, if we had a nickel for every time someone asked us about factor timing — we’d have a lot more AUM in our funds! We get the question all the time and it really is a good question. The problem is we don’t have a good answer. Our answer to the question ranges between “we’re not sure” and “not really.” The irony of this question is that it tends to come from a lot of Vanguard-ish disciples who believe passive equity investing is the only way to go.

AR: So, wait. Passive investors ask you about factor timing?

WG: Yes, all the time. Obviously these aren’t passive investors. And the question is really odd when you think about it: How can it be impossible to pick stocks that beat a passive index, and yet, simultaneously be plausible that one can successfully “time” factors to beat the market?

Anyway, what is the evidence on factor timing as far as we can tell? Instead of boring you with our own research at the outset, we recommend that everyone read Cliff Asness’ commentary on the topic. The title of his post says it all, “Factor Timing is Hard.” So that’s the short answer.

But let’s dig in and specifically examine the idea of trying to time Value and Momentum exposures. One reasonable hypothesis is the following: examine the valuation spreads between cheap and expensive firms. When the spread is wider (i.e. value firms are much cheaper than growth firms compared to historical averages), invest in Value; when the spreads are narrow (i.e. value firms are not as cheap compared to growth firms based to historical averages) invest in Momentum. Pretty logical idea – invest in Value when it’s really cheap, invest in Momentum when everything looks similar on a valuation basis.

JV: We actually examine this idea here. The short story is the following – timing Value and Momentum with valuation measures does not work very well. While some versions of these models can generate slightly higher returns, on a risk-adjusted basis there is little benefit (and this is before accounting for any tax implications incurred by shifting from Value to Momentum). This also doesn’t consider the risk of data-mining, which is arguably an important consideration. Moreover, Value and Momentum probably shouldn’t be timed, because they naturally play nicely with one another from a portfolio perspective. When Value is “yinning,” Momentum is “yanging.” (see here and here). To summarize, the minute one tries to time Value and Momentum by shifting the weights from one to the other, you lose the well-established portfolio diversification benefits that are derived from combining the two.

WG: Let me summarize: If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it!

So how do we combine Value and Momentum? We keep it pretty simple. We generally recommend that investors split their allocation roughly 50% Value and 50% Momentum, or volatility-weight the exposures. The volatility-weighting approach (i.e. Simple risk-parity) is arguably important if the exposures naturally have very different volatilities. But even if you volatility-weight the exposures, you don’t want to mess with the weights more than once a year.

AR: So factor timing is difficult. But here’s an even deeper question. Have factors themselves been arbitraged away? Charlie Ellis has a pretty compelling argument that the competition has decrased any edge and passive is the way to go.

WG: Charlie Ellis has an extremely important perspective to share. And we think it is great. Markets are competitive. Money doesn’t grow on trees. Costs always matter for an investor’s bottom line. Roger that.

But let’s circle this back to factor investing and the argument that any “edge” associated with these strategies is going to zero. But what is “edge”? If edge is the ability to scan the recent SEC filings faster and more accurately than the next guy, well, yeah, these sorts of edges are likely transient. But fast and accurate information processing doesn’t drive asset prices. Supply and demand do. Fundamentals matter, but only over long periods of time. Ben Graham refers to this as the “weighting machine” component of the stock market, whereas in the short run, the stock market is simply a “voting machine.”

Thought experiment for you: I give investors the perfect algorithm, but require that they stick with it for 20 years without flinching. How many would follow it? Definitely not 100%. In fact, in a popular blog post we look at portfolio created by “God” and look at God’s long-term investing algorithm performance. God’s algorithm rebalances every 5 years into the known winners over the next 5 year period. You can’t build a better algorithm than that! But after analyzing God’s performance, we’re pretty confident he’d be fired many times over by his clients. Lots of huge drawdowns, plenty of horrific short-term relative performance, and many reasons to fire the All-Mighty. So if God, who arguably has the best information and can process it quicker and more accurately than anybody, can’t convince his clients to stick with the program, who can?

So what’s missing from the discussion? The human element. And let’s be frank: factor investing is active investing, but implemented systematically. Let’s not fool ourselves into thinking factor investing isn’t active. And active investing mechanically will deviate from benchmarks — sometimes a lot. In fact, if active investing premiums are going to be sustainable, they have to be painful. This pain is typically derived from some sort of risk — either rational risk or risk caused by noise traders. If you want to dig deep on the topic, we have an extensive piece on this subject here.

Let’s talk about this active investing pain. When we see premiums on things, such as value and momentum, being squeezed over the past 5-, or even 10-year periods, we can’t automatically chalk that up to the Ellis argument, which roughly claims that, “There are too many CFA/PhDs armed with super-computers arbitraging away factor premiums.” If we go down the path that better technology, smarter people, and more competition are associated with arbitraging away factor premiums, we also need to then explain why Momentum went on a 10-year drought around the Civil War. Were the soldiers trading their rifles in for some modern portfolio theory lessons (even though it didn’t exist)? Why did Value get its face-ripped in the early 60’s? Maybe the publication of Fama’s dissertation thesis sparked a herd of quants to open funds (even though there weren’t any quant funds at the time)?

AR: So what you’re saying is that correlation is not causation.

WG: Pretty much. Anyone who has ever studied factors, especially Value and Momentum, should know that long-periods of relative underperformance are fairly common throughout history. A theory for decreasing factor premiums would need to reconcile why decreasing factor premiums have been observed for hundreds of years. In the case of trend-following research, there are studies going back 800 years. In short, the Ellis story is appealing at first glance, but doesn’t pass muster when you really think about it. The fact of the matter is that active factor strategies don’t work all the time, and possibly won’t work over extended times.

But does that mean these strategies won’t work in the future? Maybe, maybe not.

Assume that factor premiums are driving by some mix of fundamental risk and systematic mispricing that is costly to arbitrage. In other words, let’s assume Value works because the stocks have a higher chance of going bankrupt (fundamentally riskier) and investors tend to throw the baby out with the bathwater when they hear bad news (systematic overreaction, on average). To the extent risk preferences change, or the cost of arbitraging factors has gone down, Charlie Ellis and Co. could make a credible argument that the premiums may go away over time. On the risk preference side of the house, who knows how tastes may change or how competition could affect that aspect of Value investing. Perhaps investors don’t care that companies go bankrupt with a higher frequency and are willing to earn a smaller expected return to take on that risk. Probable? Not really. Possible? Perhaps.

Moving on to the systematic mispricing side of the house. Let’s assume, on average, Value stocks are systematically mispriced. Let’s also assume the following:

- More and more really smart people are figuring this out

- The pool of “dumb money” is shrinking because they became buy and hold forever passive

- Transaction costs are zero (to keep things simple)

Great, let’s go arbitrage the Value premium! But wait a minute. We’re managing other people’s money, and these people keep hearing from their friend’s that passive is “da bomb.” If we deviate too far from our benchmark, we’ll get fired. And this Value premium deviates WILDLY from the benchmarks — this is career suicide — I’ll pass! Don’t think this is a real problem? First, read the classic Shleifer and Vishny (1997) paper (we discuss this in a bit more detail here) and run an asset management company for a few days. Active Value strategies have dug many money manager graveyards over the years.

What’s the point? The point is that systematic mispricing, even if everyone knows about it because they have supercomputers and CFAs, does not mean that this long-term expected premium is easy to exploit and arbitrage away. In fact, to the extent investors can more easily move in and out of investments and maintain their performance-chasing habits, no amount of information edge will cause “smart money” to arbitrage away systematic mispricing. One can even make the argument that systematic mispricing might actually increase in the future. The availability of data and information have become so ubiquitous investor horizons might be further truncated. (“What does Apple look like in 10 years” becomes “What does Apple look like next week?”). We’ll have to see what the future holds for investor behavior…

AR: Let me ask a question: What would make you worry about the future of factor premiums?

WG: This is a great question with a simple answer: When we see huge pools of capital, armed with unbiased intelligent analysts and technology, who have no regard or incentives to care about relative benchmark performance, and genuine 20-year investment horizons, we’ll be worried. In other words, if miniature Warren Buffets start popping up and control a vast amount of capital, we should certainly worry about the efficacy of long-term factor premiums.

So do we think about the death of factor premiums? Of course. But let’s just say we’re not holding our breath for this to occur anytime soon. Patience and discipline will always be the purest form of alpha because they will always be in short supply.

AR: The ETF industry recently passed 2,000 funds making VMOT number 2010 or so. Is there any truth in the fears that ETFs are a destabilizing force for markets?

JV: We don’t believe that ETFs are destabilizing the markets; however, we should be aware of the impact that might have on financial markets.

For example, there are arguments that ETFs are having an effect on the trading of individual stocks. Here is a summary of a paper on the topic. The paper finds two items worth discussing. First, as ETF ownership increases in a stock, the cost of trading the stock actually increases (examining the bid/ask spread). Why? One explanation is that individuals are now purchasing ETFs instead of the stocks, so the liquidity of the underlying has simply been transferred from the stock to the ETF vehicle – this is an idea that still needs more empirical tests to confirm or deny. Second, the paper finds that asset prices reflect (1) more systematic information and (2) less asset-specific information as ETF ownership increases, which is a very similar result to a separate theory paper. So basically, as ETF ownership increases, investors (measured through earnings response coefficients) appear to care less about actual firm earnings! It should be noted that another paper finds the exact opposite result. So who really knows, there is a good chance that this is much ado about nothing.

A second item to examine is the liquidity of some ETFs. We have written about how liquid an ETF is here. High level, the liquidity of the ETF should reflect, and be similar to, the liquidity of the underlying holdings. However, this is not always the case, as some ETFs have significantly more liquidity than the underlying holdings. In general, the concern with ETF liquidity centers on those ETFs where there is a liquidity mismatch: the ETF is much more liquid than the underlying assets. As discussed here in the WSJ, common examples of this are bond ETFs. Some bond ETFs trade magnitudes more often than the underlying bonds themselves, which is a liquidity mismatch. There is a legitimate concern that in a crisis sell-off situation, investors in the bond ETFs, expecting a $0.01 spread around NAV, will be rudely awakened to the fact that they are trading illiquid securities, and will be hurt by the “true” liquidity of the investment. Only time will tell. Some hedge fund will make a ton of money, there will be 100’s of articles on how ETFs are destroying the world, but the market will adapt and adjust and everyone will move on in life. If this happens, investors will learn to pay more attention to the underlying liquidity of their ETF holdings.

A third item to discuss is the actual trading of ETFs – how does one go about buying and selling ETFs? As more and more advisors and individuals switch from a mutual fund/stock portfolio to an ETF-centric portfolio, it is important that they understand how to trade ETFs. In our opinion, too many in the marketplace believe all ETFs can be traded at any time of day and in any size – this is probably due to viewing the great bid/ask spread and liquidity on the ~ 30 large and liquid ETFs (an example being $SPY). However, the ETF flash-crash (8/24/2015) taught everyone a lesson (unfortunately for some, a real-world lesson). One needs to remember that ETFs are, by definition, derivative instruments. The price and bid/ask spread intraday are driven by the price and bid/ask spread of the underlying. So what happens when the underlying stops trading, and there is no bid/ask spread? The answer, as seen on 8/24/2015, is that the market-makers need to widen the spreads. Lesson learned from the flash-crash is to not leave open limit orders for ETFs, as this was some of the selling on that day. Another broad lesson is (in general) to not trade stock ETFs in the first 15-30 minutes of trading until the prices of the underlying have settled for the day. On average, the bid/ask spread is wider until each stock’s price (and bid/ask) settles in the morning.[3]

So in total, we don’t think ETFs are destabilizing the markets. However, they are affecting the markets and investors should understand how this works so they know the trade-offs they may face.

AR: Now with almost 3 years of ETF operational experience, and five ETFs under your belt as an independent ETF issuer, what lessons have you learned? Would you do anything differently?

JV: The first lesson we learned is that getting the market to acknowledge your ETFs exist is a challenge. You might have a great idea, but if nobody knows about it, the idea will die on the vine. ETF manufacturers need to have a plan to educate the public on their products.

Another lesson learned is that many advisors like to see a track record and a certain amount of AUM in the fund. Many require 3 years of data as well as $50mm – these requirements limit the number of potential buyers. Well, getting 3 years tracks and $50mm in an ETF is almost impossible unless you plan on burning a ton of capital and happen to have a slew of really rich friends.

Last, running an ETF business is completely different than running almost any other traditional asset management business (e.g., SMA, hedge fund, mutual fund, etc.). We have learned the operational side of the ETF business pretty well at this point and gotten extremely efficient with our workflows and understanding all the counterparties and how to play nice. The ecosystem of the business is filled with excited people who are pumped about the future of ETFs. We all feel like we are making financial services better than it has been in the past. We’re innovating, disrupting, and having a lot of fun!

WG: Would we have done anything differently? We came into the business with our eyes wide open and a full understanding that this would be a 20 year fight. We practice a culture of “cockroach” entrepreneurship, which means we want to be set up to survive a nuclear winter. That translates into low salary expectations, a desire to do more with less, and an over capitalized balance sheet to weather a 20-year storm. There are simply too many examples of asset management firms that were on their road to success, but flamed out because of financial distress, a large market drawdown, and/or they became too confident in the future. Nobody is going to kill us because we are having way too much fun and never want to get real jobs again. So we have high incentives to keep this engine going!

AR: Wes and Jack, thank you for your time and insights. It will take me a while to digest all this. Now get back to work!

JV/WG: Thanks, Tadas. We appreciate the opportunity and thanks for helping us fulfill our mission to empower investors through education.

*Author controls positions in VMOT.

[1] Note we are not discussing an attempt to time the market using valuations. Here are a few posts we have written on that topic: here, here, here, and here.

[2] Here is our take on an interesting study on the performance of low volatility investing. Historically, low volatility investing has been associated with Value investing. When this link has broken, i.e. when low volatility is “expensive” (which it currently has), the returns to a low volatility strategy have struggled in the future.

[3] Note there are a few exceptions, such as SPY which (in general) always has a very tight bid/ask spread.