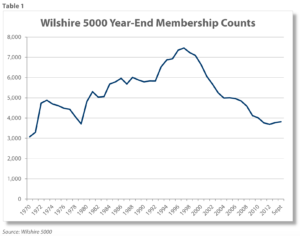

The number of publicly traded US companies has been shrinking since 1996. So the decline of the US public company should not be a shock to anybody. The Wilshire 5000 Total Market Index, which used to hold 5000 stocks, as of September 30, 2016 only held 3515.

Source: Wilshire Associates

Way back in 2011 Felix Salmon writing at Wired wrote about the reluctance of tech companies to come public. In 2012 at NYTimes Salmon wrote:

Today, however, stock markets, once the bedrock of American capitalism, are slowly becoming a noisy sideshow that churns out increasingly meager returns. The show still gets lots of attention, but the real business of the global economy is inexorably leaving the stock market — and the vast majority of us — behind.

Last year I asked in a post: Where did all the listings go? At that point in time it was difficult to see much reason to believe this trend would turn around. Academia has also taken note of the trend and two recent papers talk to this very issue.

The first paper “Evolving Difference Among Publicly-Traded Firms in the United States, 1960-2015” by Jose Maria Barrero sets the scene by noting the shift toward larger companies, the rising prominence of tech companies and the decreased chance of survival for any particular company. The second paper “Is the American Public Corporation in Trouble” by Kathleen M. Kahle and Rene M. Stulz is more pointed in in its conclusions. From the abstract:

We examine the current state of the American public corporation and how it has evolved over the last forty years. There are fewer public corporations now than forty years ago, but they are much older and larger. They invest differently, as the importance of R&D investments has grown relative to capital expenditures. On average, public firms have record high cash holdings and in most recent years they have more cash than long-term debt. They are less profitable than they used to be and profits are more concentrated, as the top 100 firms now account for most of the net income of American public firms. Accounting statements are less informative about the performance and the value of firms because firms increasingly invest in intangible assets that do not appear on their balance sheets. Firms’ total payouts to shareholders as a percent of net income are at record levels, suggesting that firms either lack opportunities to invest or have poor incentives to invest. The credit crisis appears to leave few traces on the course of American public corporations.

First off both papers highlight the problem with facile comparisons between an index today, like the S&P 500, and the index 40 or 55 years ago. Second both papers describe a financial marketplace that has seemingly failed individual investors. We should not be surprised that open-end mutual funds are fishing in the private market for growth opportunities. The question is what to do about it?

Morgan Housel at the Collaborative Fund, a venture capital firm, has a new whitepaper out that discusses these very issues. Housel ably discusses the history of this phenomenon and notes why the dearth of IPOs is an issue to investors. Housel writes:

Companies that could have broader and deeper access to capital in public markets stay private because public markets have been so unforgiving, and public investors are stuck with a less-dynamic set of companies to invest in at the very moment they need public-market returns to fund their retirements.

Maybe the most interesting part of the whitepaper is when Housel proposes solutions to this seemingly intractable problem. The solutions are in three big buckets.

- A capital-gains tax structure that truly incentivizes patient capita;

- A more inclusive and open IPO process;

- A whole new system, i.e. an altogether new stock exchange that aligns investor and company incentives.

In some ways this problem is kind of perverse. Today we have given individual investors a set of tools heretofore unavailable to institutional investors, 20 or even 10, years ago. Investors today can handle a more robust and vibrant IPO market devoid of Wall Street book-running. Investors today can handle new market structures that do not incentivize high frequency trading. CEOs today may not want to run a public company but investors today could handle a lot more of them that do.