Sherlock Holmes is one of the most beloved characters in fiction including a 2012 revival. Through acute observation Holmes is able to use abductive and deductive reasoning to bring resolution to all manner of mysteries. An appeal to evidence, and reason, is only display in the so-called police procedural that is a staple of network television. In a typical episode the police use all manner of evidence gathering to identify and apprehend the perpetrator(s). In the end, evidence usually wins out.

It is ironic that we love these types of stories so much. Because in our own lives we are woefully unable to come to terms with facts that may contradict our own internal narratives. Elizabeth Kolbert in a recent New Yorker article, “Why Facts Don’t Change Our Minds,” summarizes the findings from three recent books that demonstrate our inability to deal with reality.

For example, for some inexplicable reason, the anti-vaccine movement is once again gaining some steam. (See also: Washington Post, New York Times, NOS) One of the reasons why people have a tendency to remain wedded to their earlier believe, despite an avalanche of evidence to the contrary, is our brain chemistry. Kolbert writes:

They [Jack and Sara Gorman authors of Denying to the Grave: Why We Ignore the Facts That Will Save Us] cite research suggesting that people experience genuine pleasure-a rush of dopamine-when processing information that supports their beliefs. “It feels good to ‘stick to our guns’ even if we are wrong,” they observe.

If that is the case it probably shouldn’t be surprising we see groups of people clinging to false beliefs contrary to the evidence. One of the reasons we are able to cling to outdated beliefs is that we selectively experience data and evidence. Confirmation bias, explains why we continue to dismiss new evidence. Kolbert writes:

If reason is designed to generate sound judgments, then it’s hard to conceive of a more serious design flaw than confirmation bias…To the extent that confirmation bias leads people to dismiss evidence of new or underappreciated threats-the human equivalent of the cat around the corner-it’s a trait that should have been selected against. The fact that both we and it survive, Mercier and Sperber [authors of The Enigma of Reason] argue provides that it must have some adaptive function, and that function, they maintain, is related to our “hypersociability.”

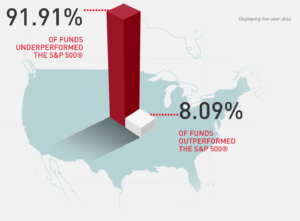

For the moment our hypersociability is working in the direction of evidence-based investing. That is, investors are taking money out of actively managed funds and putting those funds to work in passively managed funds. In this earlier post I argue there was some sort of tipping point after the global financial crisis that made index-centric investing seem like the way to go.

It wasn’t any single paper, argument or data point that made a significant number of people to embrace index investing. At some point the accumulated wisdom of investment professionals made it possible for investors to take on as their own believe that indexing work. Kolbert writes:

People believe that they know way more than they actually do. What allows us to persist in this belief is other people. In the case of my toilet, someone else designed it so that I can operate it easily. This is something humans are very good at. We’ve been relying on one another’s expertise ever since we figured out how to hunt together, which was probably a key development in our evolutionary history.

Vanguard, in large part, acquired the expertise on how to run index funds efficiently. By “hiding the technology in the back” Vanguard has made this type of index-centric investing easy to do. In so doing they have made it easier for individuals to believe that in their own knowledge and expertise.

Source: S&P (as of June 30, 2016)

We all want to feel that dopamine rush from having evidence confirm our prior beliefs. It just so happens that all the evidence of late has all been in favor of indexing.